** an informational piece on Hip Impingement and Labral Tears**

Hip Impingement and Labral Tears

Impingement is the word used to describe an abnormal contact between two surfaces, which often causes pain. In the hip, this can be anatomical or functional. In anatomical (femoroacetabular) impingement, there is pathological bony contact between the acetabulum (hip socket) and the head of the femur (long thigh bone).

There are three types of femoroacetabular impingement:

Pincer: This type of impingement occurs because extra bone extends out over the normal rim of the acetabulum (socket) and the femoral head (ball) abuts against this rim sooner in the range of motion than with a normally shaped rim.

Cam: In cam impingement, the femoral head (ball) is more oval or egg shaped and cannot rotate smoothly inside the acetabulum (socket).

Combined: Both cam and pincer impingement are present.

Functional impingement defines a suboptimal anterior (forward) positioning of the femoral head (caused by muscle imbalances and abnormal movement mechanics) which, in turn, causes impingement of normal femoroacetabular motion. Cartilage damage, arthritis, or a labral tear are unfortunate consequences of impingement.

Labral Tears

Femoroacetabular (hip) labrum: A ring of cartilage that lines the ball and socket of the hip joint. It gives the hip stability, protects the articular surfaces of the joint, and provides proprioception (the unconscious perception of where the body is in space). Proprioception is important to ensure a person employs correct movement pattering.

Causes of labral tears: A labral tear results when a part of the labrum separates or is pulled away from the socket. This can be the result of:

direct trauma - e.g. motor accidents, falling with or without a hip dislocation, slipping

sporting activities that require frequent external rotations or hyperextension - e.g. ballet, soccer, and hockey, running and sprinting

Specific movements including torsional or twisting movements, hyper abduction, hyper extension, and hyper extension with lateral rotation

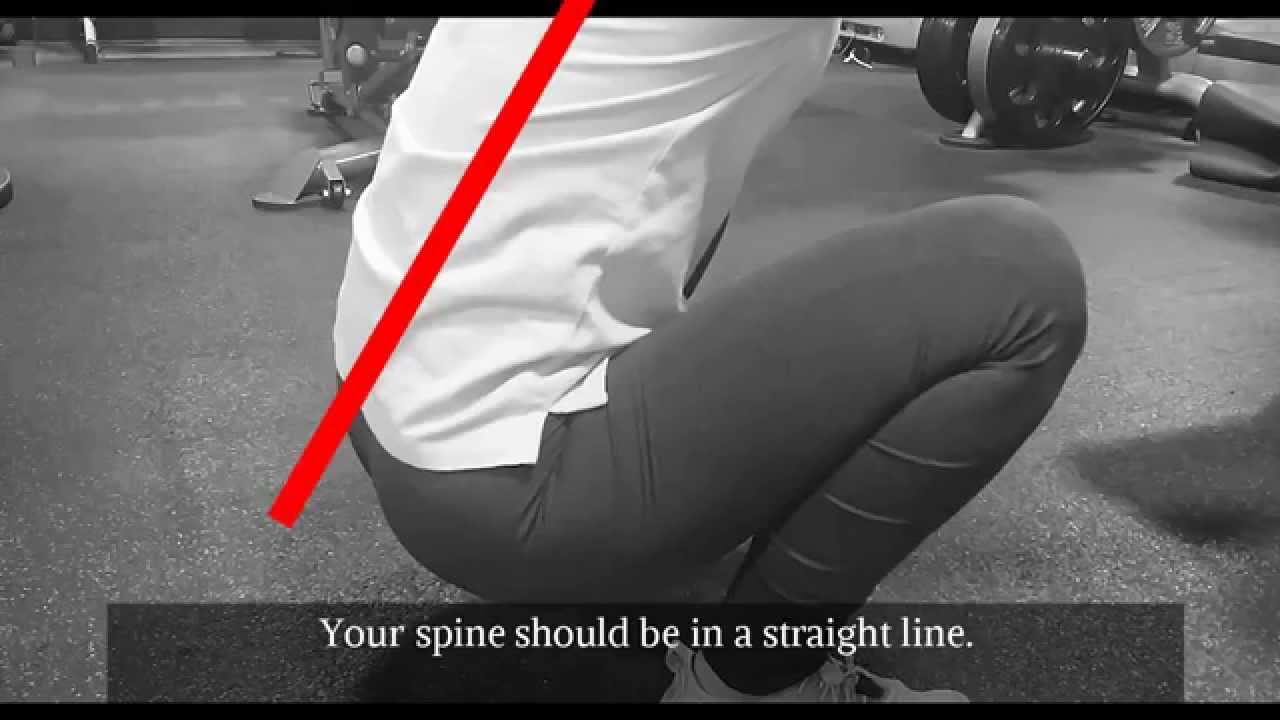

Improper technique with repetitive activities (such as squatting)

Excessive volume of activities

STRUCTURAL RISK FACTORS FOR THE CONDITION INCLUDE:

Acetabular dysplagia

Degeneration of the labrum

Capsular laxity and hip hypermobility

Femoroacetabulr impingement

SYMPTOMS

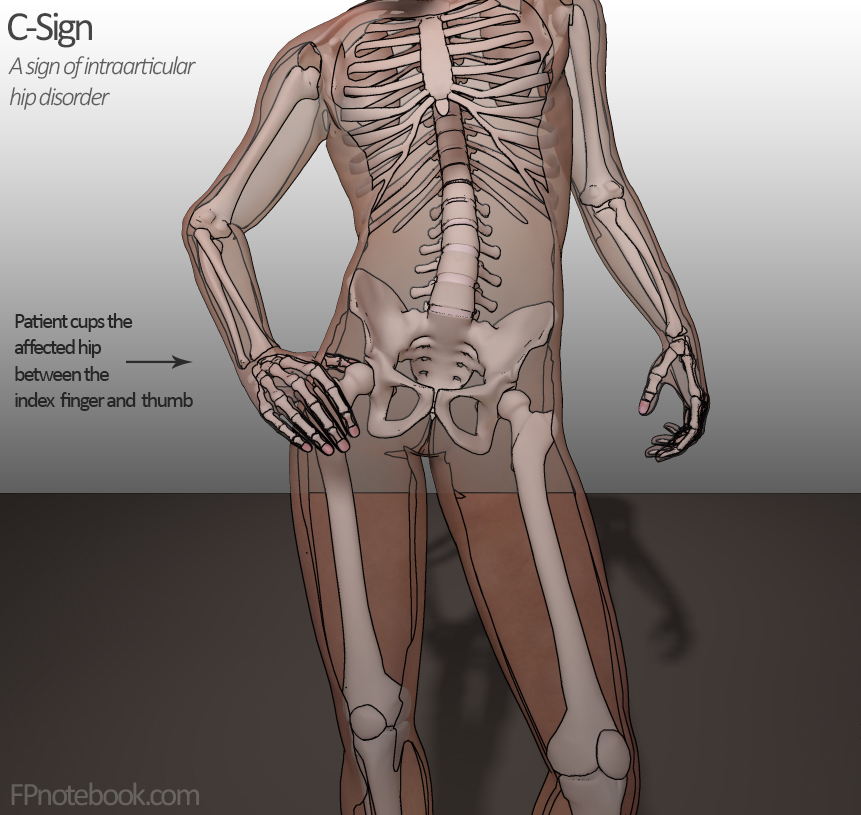

In the early stages of this condition, patients are often unaware that something serious is going on as there may be no symptoms or any symptoms that are present may be mild or vague. Some typical symptoms of hip impingement include:

stiffness in the thigh, groin, or hip

deep aching in groin or buttock

sharp pain in the groin or buttock when the thigh is moved close to the body beyond 90°

sharp pain in the groin or buttock when the thigh is moved across the body toward the opposite shoulder

pain with sitting for long periods of time

difficulty with weightbearing on the affected leg

pain at rest and/or with activity

pain during and/or after sexual activIty

pain during or after sports

low back pain and/or sacroiliac joint pain

knee pain

DIAGNOSIS

AN ACCURATE DIAGNOSIS OF HIP IMPINGEMENT IS CRUCIAL.

If left untreated, the condition can lead to abnormal movement mechanics, chronic pain, cartilage or labral damage and in some cases, osteoarthritis.

Diagnosis begins with a complete medical history and a physical examination. During the physical exam, strength, tissue tenderness, range of motion of the hip joint and presence of impingement will be assessed. Other tests may be required, including:

Radiography (X-ray) which produces two-dimensional images of the hip joint

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which produces a three-dimensional image including soft tissue, cartilage and labrum

Computed tomography (CT) scan which takes a series of small images at different angles and then applies a computer algorithm to construct a three-dimensional image of the hip.

TREATMENT

BOTH ANATOMICAL AND FUNCTIONAL HIP IMPINGEMENT RESPOND WELL TO PHYSICAL THERAPY INTERVENTION.

Restoring motion, improving muscle balance, and returning a patient to more correct movement mechanics and motor patterns are all key in this care. Patient education about correct rehabilitation exercises and stretches as well as managing outcome expectations are also included in the care of the hip impingement patient.

In some cases, anti-inflammatory methods are used. This can include cortisone injections or oral medication. Some patients also see improvement when they combine physical therapy intervention with acupuncture, massage therapy, or other body-work.

After a course of physical therapy, a patient with anatomical impingement may elect to have surgery. In these cases, a course of physical therapy is recommended following the procedure to not only help in restoring range of motion and strength but also to correct improper motor patterns that developed when the patient was having pain or weakness prior to surgery.